Research code: https://github.com/pranavc28/self-awareness-grpo

LLM: openai/gpt-oss-20b

Datasets: https://github.com/tdiggelm/climate-fever-dataset, https://fever.ai/download/fever/train.jsonl, https://github.com/TalSchuster/VitaminC

Claims

GRPO with calibration-aware rewards can improve NA recall by >10% on in-domain fact verification tasks. With effective Reinforcement Learning techniques, it is possible to make Large Language Models (LLMs) more self-aware, and better at letting users know when they cannot provide a high confidence response to a request. We will call such an outcome “not enough information/not applicable” (NA). Such an outcome will be crucial, as AI embeds itself in more workflows, to gain more trust in situations where an incorrect outcome such as PASS/FAIL will worsen the user experience.

Self-awareness transfers across domains: training on dataset A improves NA recall on unrelated dataset B. I also propose that self-awareness is in itself generalizable. That is, test and train datasets could be on completely different topics. For example, assume we use FEVER (Wikipedia facts) for training and ClimateFEVER (climate science) for test—I would expect that the NA accuracy for both datasets would increase after training the model with just the FEVER dataset. The hypothesis is that generalization can be achieved with diverse datasets promoting regularization, which in turn reduces variance.

Motivation

Despite the increased usage of LLMs in production workflows, frontier AI research labs do not seem to publish empiracal research, or configurable features, around when these models should not give an answer. After working on augmenting real marketing and security workflows at Google, I learnt that it is indeed important for these models to inform users when the models have low confidence in their results. This is something that AI agentic startups may infact not need to wait for - and can be done with cheap RL on open source smaller models.

Previously, I experimented with a new framework that I called automated confidence refinement and prompting to filter out low confidence scores (TODO link). This led to a statistically significant, but low, ~4-5% gain in “not enough information” accuracy scores.

The next step was to go deeper in the training stack, with RL being the ideal and cheapest candidate. As opposed to fine tuning, which focuses on cross entropy loss on large labelled datasets, I wanted to experiment with custom rewards. The reason being that I wanted to use verbal confidence scores from the LLM and guide it towards returning outcomes where it is not sure about the solution.

Methodology

Training Approach. We employ Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) to train a language model for fact verification with self-aware confidence calibration. Unlike standard fine-tuning which optimizes only for classification accuracy, this approach optimizes for correctness and calibration—the model learns to express high confidence when correct and low confidence when uncertain. For each training example, I sampled 8 completions at temperature 0.2, compute per-sample rewards, and calculate advantages relative to the group mean. This relative advantage formulation enables the model to learn which response strategies yield better outcomes without requiring absolute reward scales, making the optimization more stable across diverse claim types.

Technical Implementation. We train using LoRA (rank 32) on a 20B parameter base model for 160 steps with batch size 32. Each training step processes 256 total completions (32 examples × 8 samples). The model receives structured prompts containing the claim, retrieved evidence sentences, and instructions to output a label (PASS/FAIL/NA) with a confidence score between 0 and 1. We probe the model’s label distribution by computing log-probabilities for each label token given the prompt prefix, converting these to normalized probabilities via softmax for use in the reward computation. This probing mechanism provides the internal probability estimates needed for alignment and consistency penalties.

Experiment

Datasets.

Training Sets. We employed 2 different training strategies. The first involved training on just the FEVER dataset of 1,000 examples. The second used a balanced mixed dataset of 1,020 examples (340 per dataset, equally split across NA/PASS/FAIL labels) for regularization. The hypothesis was that generalization can be achieved with diverse datasets promoting regularization, which in turn reduces variance.

Validation Sets. We evaluate on three fact verification benchmarks spanning different domains to test generalization. FEVER (Fact Extraction and VERification) contains claims derived from Wikipedia with human-annotated labels and evidence sentences. VitaminC tests factual consistency using Wikipedia revision pairs, where claims may be supported, refuted, or have insufficient evidence based on subtle textual changes. ClimateFEVER focuses specifically on climate science claims, presenting a domain-specialized challenge. For evaluation, we hold out separate sets of 1,000 examples per dataset using a different random seed to ensure no overlap with training data.

Evaluation Protocol. We compare two conditions: a control model (the base 20B model with no fine-tuning) and our GRPO-trained checkpoint. Both models receive identical prompts and evaluation examples to ensure fair comparison. Each model outputs a label and confidence score; we record accuracy (whether the predicted label matches ground truth) and the stated confidence. This allows us to analyze not just whether GRPO improves accuracy, but whether it produces better-calibrated confidence estimates—meaning the model’s confidence should correlate with its actual likelihood of being correct.

Metrics and Analysis. Beyond raw accuracy, we compute calibration metrics to assess whether confidence scores are meaningful. A well-calibrated model should be correct approximately 80% of the time when it claims 0.80 confidence. We examine confidence distributions stratified by outcome (correct vs. incorrect predictions) and by label type (NA/PASS/FAIL), as the model may exhibit different calibration patterns for different prediction types. We also analyze the reward component trajectories during training to understand how the model learns to balance accuracy against calibration, and whether the warmup schedule successfully prevents early collapse into degenerate solutions.

Reward Function Deep Dive in GRPO

First, we used GRPO because of the limited dataset size for cost reasons. Second, by selecting a higher temperature I wanted to explore the dimension space and test how frequently an LLM would have different answers.

The reward function combines seven components designed to shape well-calibrated, self-aware predictions. The primary signal is an accuracy reward (+2.0 for correct labels, −1.0 for incorrect). We add a log-probability shaping term that encourages the model’s internal distribution to place mass on the gold label. For calibration, we use a proper scoring rule (Brier-style): the model is penalized proportionally to the squared distance between its stated confidence and the ideal target (1.0 if correct, 0.0 if incorrect). An alignment penalty discourages mismatch between the model’s stated confidence and its probed probability for the emitted label—this prevents the model from claiming confidence it doesn’t internally hold. Additional penalties discourage false “Not Enough Info” predictions when evidence exists and penalize inconsistency between the emitted label and the model’s argmax prediction. Calibration and alignment terms are warmed up over 50 steps to avoid overpowering the accuracy signal early in training.

The total reward for each sampled completion is:

\[ R = R_{\text{acc}} + R_{\text{shape}} + R_{\text{cal}} + R_{\text{align}} + R_{\text{na}} + R_{\text{cons}} + R_{\text{fmt}} \]Component Definitions:

\[ R_{\text{acc}} = \begin{cases} +2.0 & \text{if } \hat{y} = y \\ -1.0 & \text{if } \hat{y} \neq y \end{cases} \]\[ R_{\text{shape}} = 0.1 \cdot \log p(y) \]\[ R_{\text{cal}} = -0.25 \cdot (c_{\text{verbal}} - \mathbb{1}[\hat{y} = y])^2 \]\[ R_{\text{align}} = -0.15 \cdot |c_{\text{verbal}} - p(\hat{y})| \]\[ R_{\text{na}} = \begin{cases} -2.0 & \text{if } \hat{y} = \text{NA} \land y \neq \text{NA} \land \text{evidence exists} \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \]\[ R_{\text{cons}} = \begin{cases} -0.25 & \text{if } \hat{y} \neq \arg\max_\ell p(\ell) \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \]\[ R_{\text{fmt}} = \begin{cases} -0.25 & \text{if output format invalid} \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \]Where:

- \(\hat{y}\) is the emitted label parsed from the model’s output

- \(y\) is the ground truth label

- \(c_{\text{verbal}} \in [0, 1]\) is the model’s stated verbal confidence (the confidence score the model explicitly outputs)

- \(p(\ell)\) is the model’s probed probability for label \(\ell\), obtained by computing softmax over log-probabilities of each label token

Component Explanations:

| Component | Purpose |

|---|---|

| \(R_{\text{acc}}\) | Primary accuracy signal—rewards correct classifications, penalizes incorrect ones |

| \(R_{\text{shape}}\) | Soft shaping term encouraging the model’s internal distribution to favor the gold label |

| \(R_{\text{cal}}\) | Brier-style calibration penalty—confidence should approach 1 when correct, 0 when wrong |

| \(R_{\text{align}}\) | Alignment penalty—stated confidence should match the model’s own probability for its prediction |

| \(R_{\text{na}}\) | Prevents collapse to “Not Enough Info” when evidence clearly supports or refutes the claim |

| \(R_{\text{cons}}\) | Discourages reward hacking where the model emits a label different from its internal preference |

| \(R_{\text{fmt}}\) | Encourages adherence to the structured output format |

Training Curves

FEVER only dataset training

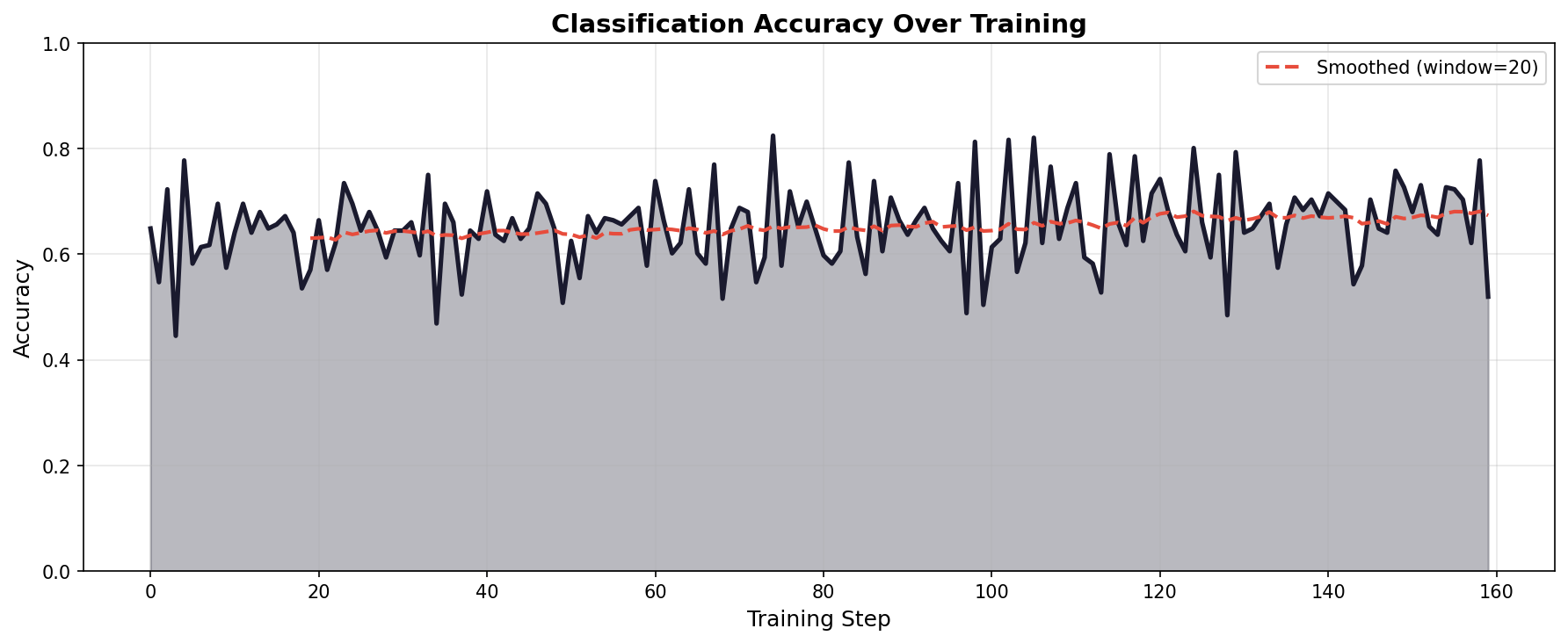

Fig 1. Accuracy curve over training for FEVER-only training dataset

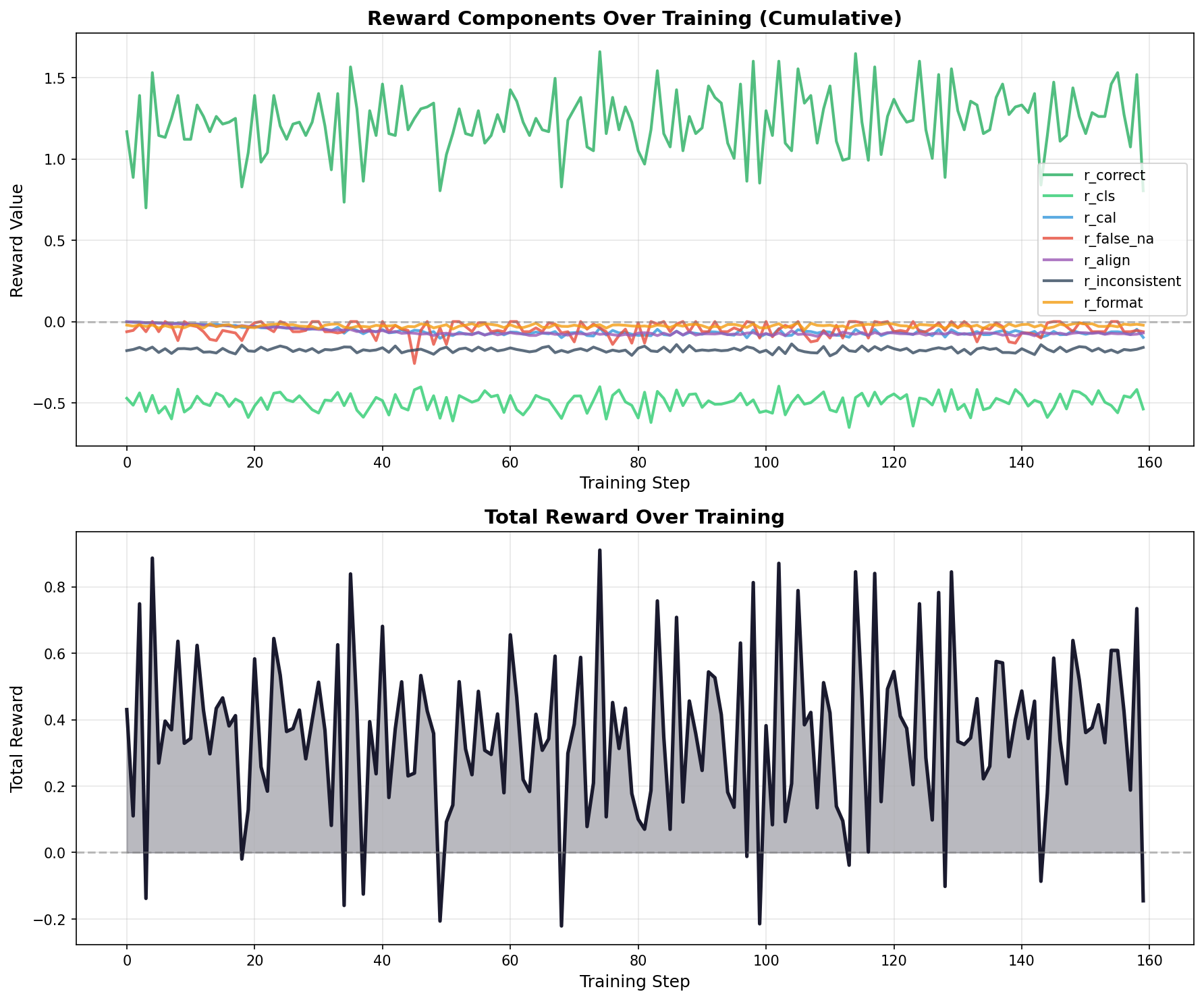

Fig 2. Rewards cumulative curve over training for FEVER-only training dataset

MIXED training dataset

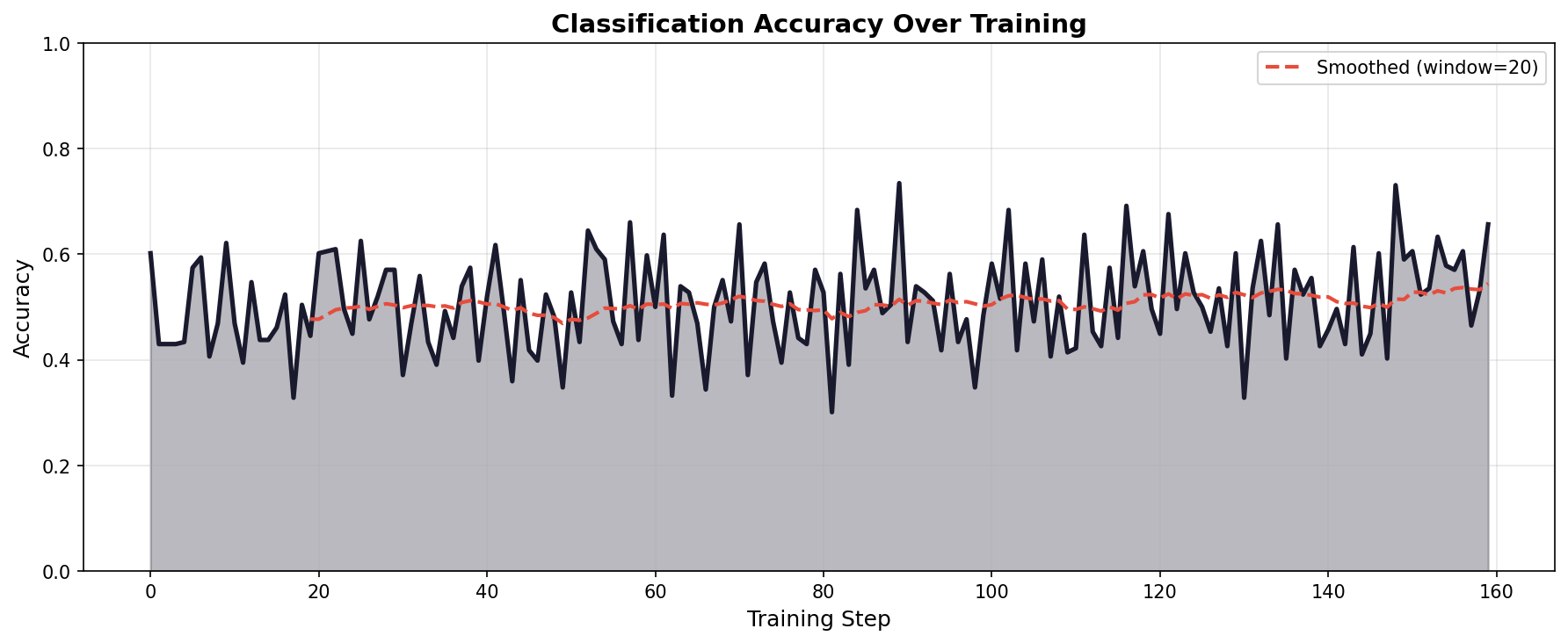

Fig 3. Accuracy curve over training for mixed training dataset

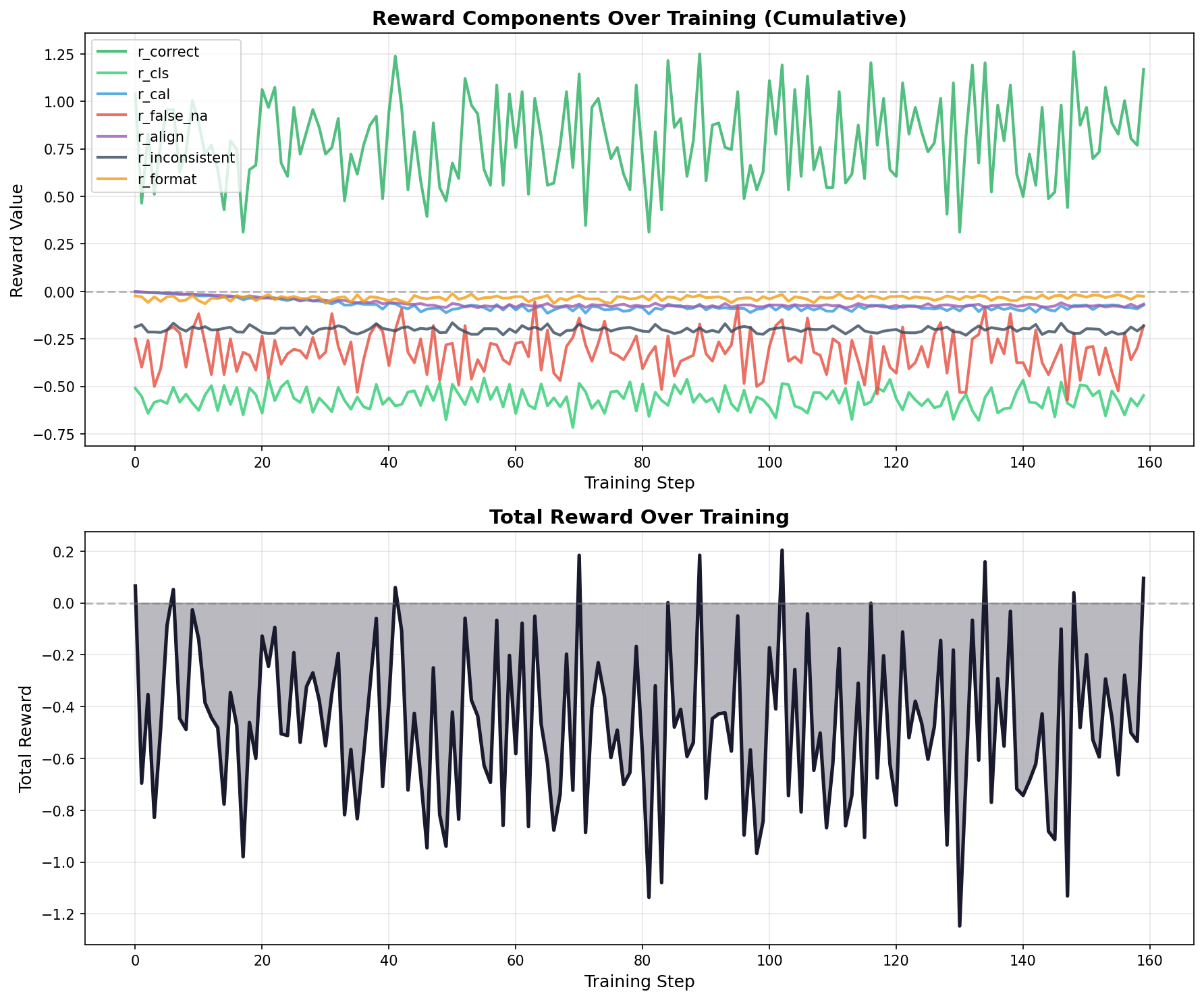

Fig 4. Rewards cumulative curve over training for mixed training dataset

Discussion

Accuracy Dynamics. The accuracy curves reveal different learning patterns between training regimes. FEVER-only training shows rapid improvement, jumping from 65% to ~78% within 30 steps before stabilizing. Mixed training exhibits more volatility—accuracy oscillates significantly early on (dropping to 43% at step 1) before gradually recovering. By the final step, FEVER-only achieves 77.7% batch accuracy while mixed training reaches 65.6%.

Reward Component Evolution. The cumulative reward plots show how components contribute across training. In FEVER-only training, the accuracy reward (r_correct) stabilizes around 1.2-1.5, while the false-NA penalty (r_false_na) stays small (−0.06). Mixed training shows higher false-NA penalties (−0.18 to −0.36), reflecting the challenge of distinguishing uncertain cases across domains. The calibration component (r_cal) grows more negative in both cases as warmup completes.

Generalization Trade-offs. The shaping term (r_cls) reveals domain-specificity differences. FEVER-only achieves r_cls ≈ −0.46 while mixed shows r_cls ≈ −0.55, indicating sharper internal predictions when trained on a single domain. However, this sharpness doesn’t transfer—FEVER-only training shows strong in-domain gains but fails to generalize.

Results

Calibration Metrics

We evaluate three self-awareness metrics: AUROC measures whether confidence predicts correctness (higher = better). Brier Score is a proper scoring rule for calibration (lower = better). Confidence Std measures whether the model differentiates easy vs hard examples (higher = better).

| Training | Eval Dataset | Accuracy (Base→GRPO) | AUROC | Brier | Conf Std | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEVER-only | FEVER | 66.0% → 72.4% | 0.430 → 0.478 | 0.301 → 0.293 | 0.166 → 0.219* | GRPO 3/3 |

| FEVER-only | VitaminC | 70.6% → 69.6% | 0.494 → 0.474 | 0.275 → 0.282 | 0.153 → 0.154 | Base 2/3 |

| FEVER-only | ClimateFEVER | 60.3% → 59.1% | 0.519 → 0.489 | 0.321 → 0.329 | 0.159 → 0.171* | Base 2/3 |

| Mixed | FEVER | 66.0% → 79.7% | 0.430 → 0.430 | 0.301 → 0.257 | 0.166 → 0.234* | GRPO 2/3 |

| Mixed | VitaminC | 70.6% → 69.5% | 0.494 → 0.485 | 0.275 → 0.286 | 0.153 → 0.170* | Base 2/3 |

| Mixed | ClimateFEVER | 60.3% → 59.1% | 0.519 → 0.508 | 0.321 → 0.318 | 0.159 → 0.180* | GRPO 2/3 |

* indicates p < 0.05 for Levene’s test on confidence variance. Bold indicates the better value.

Statistical Significance (Paired Bootstrap, n=10,000)

| Training | Eval Dataset | Macro F1 (Δ) | Accuracy (Δ) | NA Recall (Δ) | p-value | Significant? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEVER-only | FEVER | +0.068 | +6.3% | +14.9% | 0.0000 | ✅ Yes |

| FEVER-only | VitaminC | −0.006 | −0.6% | −0.6% | 0.4934 | ❌ No |

| FEVER-only | ClimateFEVER | −0.008 | −0.8% | −0.2% | 0.4034 | ❌ No |

| Mixed | FEVER | +0.138 | +13.5% | +29.3% | 0.0000 | ✅ Yes |

| Mixed | VitaminC | −0.006 | −0.7% | −1.5% | 0.5328 | ❌ No |

| Mixed | ClimateFEVER | −0.007 | −0.7% | +0.2% | 0.4768 | ❌ No |

How Significance Was Calculated

We use paired bootstrap testing (10,000 iterations) to compute p-values and 95% confidence intervals. For each bootstrap sample, we resample with replacement from paired predictions and compute the metric difference to build an empirical distribution. A two-tailed p-value < 0.01 indicates the improvement is unlikely due to chance.

Conclusion

Our results provide partial support for the original claims.

Claim 1: RL can improve LLM self-awareness. ✅ Supported. GRPO training with calibration-aware rewards produces statistically significant improvements in NA recall within the training domain. FEVER-only training achieved +14.9% NA recall (p < 0.0001), while mixed training achieved +29.3% NA recall on FEVER. The model learned to express uncertainty more appropriately when evidence was insufficient, validating that cheap RL on smaller models can meaningfully improve self-awareness without waiting for frontier lab solutions.

Claim 2: Self-awareness generalizes across domains. ❌ Not supported. Despite our hypothesis that diverse training would promote regularization and transfer, neither training regime produced statistically significant improvements on out-of-domain datasets (VitaminC, ClimateFEVER). The p-values ranged from 0.40–0.53, indicating no detectable transfer. Mixed training did show improved confidence differentiation (Conf Std) on out-of-domain data, but this did not translate to accuracy or F1 gains.

Implications. For researchers deploying LLMs, these results suggest that self-awareness calibration must be performed on in-domain data. A model trained to say “I don’t know” on Wikipedia-derived claims will not reliably do so on climate science claims. The good news: even with ~1,000 domain-specific examples and lightweight LoRA training, significant self-awareness gains are achievable. The path forward may require either (1) much larger and more diverse training mixtures, (2) explicit meta-learning objectives for uncertainty transfer, or (3) acceptance that calibration is inherently domain-specific. Which of these approaches would unlock cross-domain generalization remains an open question for future research.